An ancient icon encompassing the sanctity of life from womb to tomb

Matthew J. Milliner is professor of art history at Wheaton College

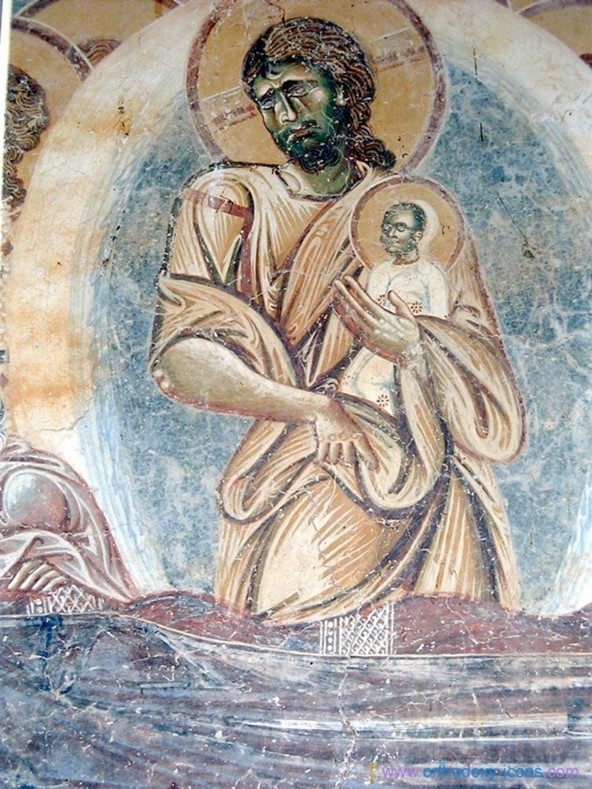

Where can we go to visualize the best imagined future of the pro-life movement? When my students ask me this, I direct them to images of the Visitation of Mary and Elizabeth, such as this freestanding statue from The Metropolitan Museum of art. Jeweled wombs show the preciousness of what lies within Mary and Elizabeth, and every pregnant woman before or after them. Or, if this is seems too symbolic, I direct them to places where the two babies are literally depicted, such as the Master of Erfut’s portrait of Mary, or this church fresco in Cyprus, where an infant John the Baptist genuflects before his Lord.

Still, I wonder if these images, beautiful as they may be, are inadequate. Considering the challenges facing those who defend the sanctity of life today, any pro-life symbol that only focuses on the early stages of life might fall short. If Canada has euthanized more than 10,000 people in 2021, with rapidly increasing numbers to come. There is special urgency to address our failed moral imagination regarding the end of life, not just its beginning. In his courageous article explaining Canada’s new policies, Ewan Goligher explains:

I distinctly recall the day when it dawned on me that those of us who refused to participate in assisted death would be regarded as physicians of questionable ethics. We might be seen as more concerned for our own personal moral hang-ups than for the welfare of the patient. Where causing death was once a vice, it was soon to be a virtue.

Is there an image that could help restore that understanding, bringing both early life and end of life issues together to galvanize the pro-life cause? There certainly is a need for such an image, if only because Canadian advertisers are making death appear to be beautiful. The fashion company Simons notoriously produced their All Is Beauty ad, advancing the “beauty” of medically assisted suicide. Seaside mourners exchange pleasantries as they usher a friend toward her voluntary exit from this life. The ad is certainly beautiful, even though what it is advising, the deliberate termination of life with full endorsement from trendy taste-makers and the government, is hideous. In his analysis of the ad, Ross Douthat clearly perceives what is at stake:

[T]he idea that human rights encompass a right to self-destruction, the conceit that people in a state of terrible suffering and vulnerability are really “free” to make a choice that ends all choices, the idea that a healing profession should include death in its battery of treatments — these are inherently destructive ideas.

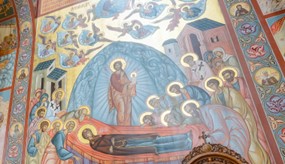

I suppose the pro-life movement might compensate for such ads with equally well-produced videos. But because the church pioneered the sanctity of human life, resisting the exposure of infants and urging care for the sick and elderly in every century since its founding, we have ancient images to draw upon as well. Why not choose an image that has already been proven, one that suggests the inviolability of life from womb to tomb? I would submit such a time-tested image to be the Dormition.

The Dormition of Mary

The story of Mary’s Dormition is less known in parts of Christian tradition, but it is certainly ancient. Protestant Christians have tended to dispute legends about the end of Mary’s life because they are not Biblical. But we can warm up to such stories if we stop to consider that they are not claiming to be on par with the Biblical text. Instead, they are loving embellishments of the Biblical accounts, comparable to dramatized shows like The Chosen today. The fact that the early church saw fit to comment upon the end of Mary’s life should at least move us to curiosity as to what they said. And what they said was beautiful. Mary, according to tradition, was laid to rest in a cave just beyond Jerusalem in the valley of Jehoshaphat, just before her assumption into heaven. Tradition relates that all the apostles showed up for the funeral, including Paul, lending unexpected resonance to Joel 3:2: “I will gather all the nations and bring them down to the valley of Jehoshaphat…” There was an underground church dedicated to this moment that is still in Jerusalem today, and the Feast Day for the celebration is 15 August

In a move that should be especially cheering to Protestants, Dormition iconography reverses Mary’s carrying of Christ. Here, the woman who once carried Jesus is now carried by him, an image resonant for any adult child who has had to care for elderly parents. What looks like an infant in Jesus’s arms is in fact Mary’s departing soul, which looks like a child. The Dormition is therefore an image of a good death. Moreover, it is an image not just of Mary’s death, but is representative of the death of all of us, when Christ will be present and hold us as well. “The “Mystery of the Virgin, now being accomplished, is our lot too,” says Andrew of Crete in his Dormition homily. “This is our frame that we celebrate today, our formation, our dissolution.”

In other words, this moment is less about claims of historical fact than an expressed need of the faithful to see what a good and natural death looks like, in God’s time, not our own.

The earliest known image of Mary’s Dormition dates to the fifth century. Clearly, Christians saw a need to depict this image frequently, as in this Byzantine ivory from the tenth century. It became so popular that is appears in Orthodox churches today all over the world. I am particularly fond of this mosaic version at the Chora Church (now the Kariye Mosque) in Istanbul.

Byzantine Dormition mosaic at the Chora Church in Istanbul (14th c.), photo by José Luiz Bernardes Ribeiro.

Because Jesus looks as if he is delivering a baby in this image, though it is the image of a funeral, it is wonderfully ambiguous, touching upon both beginning and end of life. I would like to suggest a fourfold meaning of the Dormition image, advancing it as an icon that can represent the best of the pro-life movement today.

Meaning 1 – Christ welcomes babies, and so must we: The first and most obvious meaning of this image is that Christ, who seems to be holding an infant, cares for the lives of babies during and after pregnancy. The one who said “Let the children come unto me” urges us to create a world where babies are welcomed by their parents, and where adoption is possible if they cannot be. This requires active refusal of presumably “efficient” and “compassionate” policies. When, for example, my pregnant wife was advised to take a test to screen our child for Down syndrome (a de facto encouragement toward abortion should the results be positive), we simply refused the test. The results did not matter because, as Christians, we would have welcomed the child either way. If our child had had an extra chromosome, he or she would have been welcomed into a congregation with other Down syndrome children, who constantly illustrate for us the radiant image of God.

Dormition at Kurbinovo, Macedonia (1191)

Meaning 2 – Christ cares for the dying, and so must we: Because, as we’ve seen, the Dormition image is an image of a funeral, it tells us that Christ will be there at our deaths, and he is present at the death of all human beings. We therefore must prepare ourselves for death and not fear it, but nor should we hasten it. As any hospice chaplain will report, death throes often elicit final peace with God. Death, even prolonged death, can also be a time where caretakers find new peace with those for whom they care as well. It is often a time when reconciliation is realized, where bitterness is finally overcome. These are costly lessons; indeed, they are the lessons we live to receive, and they are lessons we cannot do without. The Dormition image, with the disciples gathered from far-flung regions of the earth, represents just such a good death. They did not hasten her end, but waited for the moment where she could offer her soul back to her son and her God.

Dormition at Sopoćani. Serbia (1266).

To return to the article by Ewan Goligher, the answer to increasing euthanasia is care:

[O]ur churches can be communities where assisted death is inconceivable because the weak, the aged, the disabled, and the dying are regarded as priceless members of the community. We can be a place where those who suffer enjoy the devoted companionship, love, and support that reminds them of their value and bears them up through pain. This is, after all, what all of us long for.

I am tempted to contrast the image of Mary’s Dormition—representing a good death—with the image of Canada’s vision of what we might call “designer death.” The two are very much not the same. The Dormition’s image of a natural death is far more beautiful than what Canadian fashion designers imagine voluntary death to be.

Meaning 3 – Christ cares for all mothers, whatever their choices, and so must we: The fact that the Dormition image is also about Christ’s care for his dying mother reminds us that Christ cares tenderly for all mothers, even those who have had or will have abortions. Writing in Comment, Chris Whitford describes an organization, Avail, that is there to prevent abortions, but also to help women who have had abortions. Whitford explains:

“We offer quick solutions and pat answers—whether to “get an abortion” or “carry to term”—that keep us from facing the reality that we too are often dependent, trapped, forsaken, powerless, and lost.”

Detail of El Greco’s Dormition (1567).

Avail’s compassionate approach means that “each year, 68 to 78 percent of Avail’s reporting clients change their minds and carry their pregnancies to term.” Even so, “‘This program is not a reward for a client carrying to term,’ affirmed one staff person. Avail is called to love unconditionally.”

Christ’s care for his mother in this image tells us that Christians are summoned to care for mothers in hopes that this can prevent abortions. But if tragic abortions happen, the care must not stop.

Dormition at New Gračanica Monastery (photo: author)

Meaning 4 – Sub-Christian strategies do not befit the pro-life cause: Finally, the tender humility in the face of Christ in the face of death makes the Dormition also an image for the purification of the pro-life movement. The icon of Christ holding Mary’s soul above her spent body might also represent our dying to spent strategies so that our souls can be saved as well. What will it profit us if we achieve select legislation objectives but forfeit our souls? Some in the pro-life movement have adopted aggressive, Machiavellian tactics. Relishing the prospect of God’s chastisement of our political enemies can take the place of mandated enemy love. Criticism of such strategies is decried as naïve and unrealistic – evincing a pollyannish failure to “get our hands dirty” and get the job done. But the “whatever it takes” approach can also be shortsighted, for it fuels the pro-abortion, pro-euthanasia opposition, justifying their deployment of such strategies themselves. The pro-life movement at its best should be measured child by child, mother by mother, and elder by elder, not just by election cycles. The fight—and it is a fight—continues, but we don’t need a “champion” because we already have one; and he holds babies, mothers, and the dying in his wounded arms.